Original Post

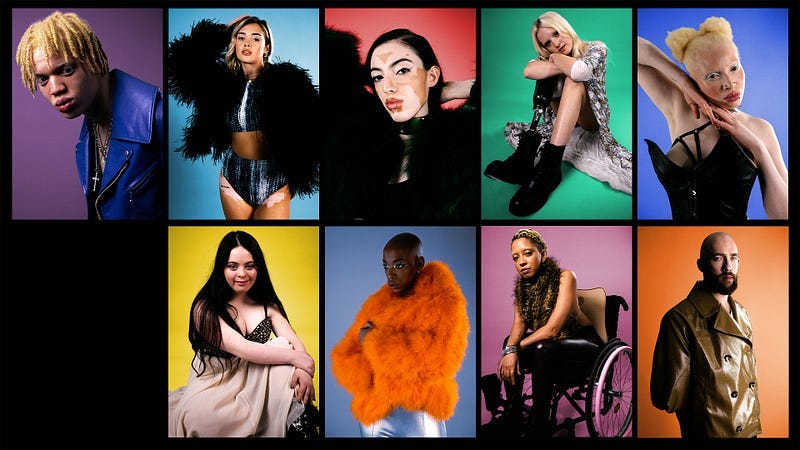

A couple months ago, I finished the ‘New Model Agency’ on Channel 4. A three-part documentary about Zebedee Talent Agency, it parades behind the scenes of the UK’s most inclusive modelling agency and its cohort of diverse models trying to make it in the world of fashion. Zebedee’s books feature models of various backgrounds, such as those with vitiligo, albinism and even physical disabilities like visual impairment or paraplegics. Just by clicking on their website and hovering on the models’ faces, a text box appears showing their model stats and different identities. I couldn’t help but remix Chef Gusteau’s refrain — “anybody can model!”

All in all, I thoroughly enjoyed the show! I found the models wonderful and incredibly funny, especially Jasroop Singh, Zebedee’s enigmatic commercial model with vitiligo. Had this show been on IMDb, I would’ve given it tens across the board! However, if you read my previous article “The Fashion Industry Doesn’t Care About Racism”, you already know how sceptical I am of media like this (hater allegations confirmed!) Although I liked the show, I implore everyone to question the media that they consume.

Episode 2 features one of Zebedee’s editorial models, Nan, who is non-binary from Yorkshire with albinism. We are privy to their magazine shoot, dressed in an assortment of garments that are reminiscent of Vivienne Westwood’s punk revolution, complementing Nan’s eccentric, pierced look. Upon the release of the issue, they flick through the pages, remarking that their presence in the magazine is a shift away from ‘stereotypical and traditional standards of beauty; of white, blonde, European with blue eyes.’ This alludes to the show’s opening credits; big bold text flashing before our eyes as the models narrate — “The Face of Fashion is changing,” and “Inclusive Revolution.” This messaging sounds all too familiar.

It took me back to my fan account days in Autumn 2018. At the time, transgender model Leyna Bloom launched her failed campaign to be Victoria’s Secret first trans model. She tweeted: “Trying to be the 1st Trans model of color [sic] to walk a #VictoriaSecret [sic] Fashion show.” followed by her bikini polaroids. In an interview to Yahoo Lifestyle, she describes how the VS gig is a dream of hers but also would be a moment for all her trans sisters. In an indirect response to her proposal, the disgraced former CMO of L Brands (Victoria’s Secret’s parent company) Ed Razek retorted that he wouldn’t put trans models on the runway because “the show is fantasy,” causing a brouhaha that the brand has never fully recovered from. Of course, they then caved in to the critiques and hired Valentina Sampaio who then passed the baton to Alex Consani, which to the critically blind, is a commitment of trans models to the VS fantasy.

Razek wasn’t wrong to call the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show a ‘fantasy’. As I explained in my previous article, notable sociologist, Ashley Mears, argues that fashion is built on the illusion of glamour that models help to facilitate. In doing so, the model’s body takes on cultural meaning defined by producers of fashion; be it casting directors, bookers and photographers. These producers engage socially to define sporadic trends, creating the concept of the ‘look’, with scouts acting as explorers to discover girls that can be moulded to adhere to these trends, usually in the form of cis, white and thin. In other words, in signing a modelling contract, the model has agreed to her commodification. In this commodification process, the ideal gender is constructed because modelling is the “professionalisation of gender,” Mears explains.

Judith Butler famously rationalised gender as a performance, inspired by Simone De Beauvoir’s stance that one becomes a woman as opposed to being born one. Fashion becomes the playing field where these theories interact, where women’s bodies are given ‘cultural value as objects of sexuality and beauty’. In every advert, runway show and editorial, the models being on display adhere to the objectification of women, emphasised by the fact that mind and body are intrinsic to model work. Whether the model feels objectified is irrelevant as socially, the display of women’s bodies is normalised and promoted by society, where women are often remunerated highly compared to their male counterparts as mere compensation. Thus, gender in fashion celebrates women being on display but coupled with the lack of diversity, cis, white and thin becomes idealised gender on display.

In theorising racial disparity in fashion, Mears categorises the few chosen top models of colour as ‘ethnicity lite’ or ‘ethnicity exotic’. The former refers to looks that have enough proximity to whiteness to be valuable whereas the latter explains the fetishization of otherness. I propose the concept of ‘gender lite’ and ‘gender exotic’: the construction of transexuals falls in line with the former and non-binary and gender queerness as the latter. In this mode of thinking, transexual models experience an interesting gender reversal that feels almost too affirming to be true. Where women are socialised to be perceived and scrutinised, trans female models are privy to a change from active subjects to passive objects, further emphasised by their requirement to be on display to sell luxury goods. However, this change can only be successful so long as they fit the narrow moulds of idealised gender. Despite not being cis women, Alex Consani and Colin Jones are able to pass as thin and blonde cis women. In fact, their success reinforces the concept of ‘gender lite’; so, long as they have a proximity to normative gender, they can be packaged and sold to audiences as cis women, in what Erique Zhang refers to as ‘successful deception’.

Likewise, trans male models experience a similar wakeup call where their social shift from object to subject decreases their economic value and so their demand lessens, and in some extreme cases, ceases. The most obvious case is that of Nathan Westling, whom pre-transition, was always featured on every major runway. Despite a British Vogue cover in August 2022, it feels like fashion has completely forgotten about him. For a lack of a politer explanation, Nathan cannot sell the glamour of the industry because he disrupts the romance of fashion. He doesn’t look like an editorial male model, who is thin, boyish with a chiselled jaw. Despite the fact he passes very well socially, in fashion, he is an unsuccessful deceiver because of his distance from normative gender. In this way, ‘passing’ becomes an important metric in signing and hiring transexual models, making trans visibility conditional. It’s also important to note that that the disparity in successful trans female to male models only reinforces gender in celebration of the objectification of women as opposed to an acceptance of trans women.

Contrastingly, non-binary as a gender performance is the kind of complexity that gives the industry a brain aneurysm. They just still haven’t cracked it! So, they resort to fetishization; where non-binary models are presented as the antithesis to traditional models but are restricted to the aestheticized vision of ‘difference,’ in which case, is usually the off-brand version of androgyny. This manifests in tensions between masculine and feminine: a feminine model draped in an oversized suit and its distant cousin, the masculine model wearing a dress. Don’t get yin-yang from Shein!

Although, to the industry’s credit, many agencies have tried to show their allegiance to non-binary models by not categorising their model boards by gender. Rather, opting for the all-encompassing term ‘talent’, or ‘models.’ Notwithstanding, their practice of branding their non-binary models weakens their efforts. Grace Valentine is a talented non-binary top model signed to Chapter Management in London, who are one of the very few agencies to not only list their talent’s pronouns but have a gender-neutral board. Yet, it seems that Grace’s book doesn’t reflect this commitment as they are constantly featured in feminine-presenting editorials. A model book is useful to communicate to clients a model’s brand thus, Grace’s work reflects the aestheticized vision of non-binary models with long hair that constrains them to womenswear, branding them under similar gender norms as female models. Compare them to Kai Isaiah Jamal, masc-presenting British model, whose blackness is more conspicuous than Grace’s. Blackness is already at odds with traditional white femininity, so, it brings to question whether their book being overwhelmingly menswear is true acceptance of their identity or trapping them in masculine presentation. The difference between these two prominent non-binary models suggests one-dimensional ‘visual signifiers’ of a gender performance that is complex and multifaceted. It blurs the lines between sheer ignorance and just outright misgendering.

Moreover, structurally, fashion hasn’t catered to these gender changes. If we consider the gender wage gap in modelling, female models are more in demand and more important to brands in communicating exclusivity and luxury. But with the influx of non-binary models, a model’s worth is still quantified by the gender binary, where their acceptance into womenswear or menswear defines which rate they’ll receive. This is another way that fashion has codified the white hegemony, propagated by producers who majorly do not belong to the identities they aestheticize. (Although models do not openly discuss pay and rates, one can assume from the kind of work they do. Being featured in womenswear campaigns by luxury designers is guaranteed a lot more money in comparison to a menswear campaign thus, this metric is useful to suggest the wage gap.)

However, the media continues the myth that trans models present a radical shift away from normative gender, breaking down the solid glass ceiling stopping trans people from succeeding. This is where Leyna Bloom and Nan’s thinking hails from, so it’s to no surprise that trans models themselves repeat these vacuous words almost as a self-soothing healing salve. Their individual success becomes a communal duty to show that “anybody can model!” no matter which identity they possess. Of course, to an extent, this type of messaging is important to give trans people hope. Hortense Spillers explains that black people cannot afford to be individualistic, theorising the concept of “the one”. Where the “one” understands that they are a subject and desires private existence, which doesn’t necessarily remove their membership from wider society, the ‘individual’ is the synecdochic supreme of the macrocosm it hails from. I believe that trans models follow a similar trajectory by virtue of countering negative media stereotypes against trans people, positioning them as the optimal example of transness. So, where there is a need and function for trans representation, the problem lies with the contrived construction of ‘transgender’ that homogenises all trans people, producing tokens in the industry who act as symbolic champions for change that barely affects fashion politique.

Part of institutionalised diversity is the neoliberal assumption that media representation is synonymous with political liberation, allowing brands to rehabilitate themselves as trans allies. This is why Zhang calls the inclusion of trans models a double-edged sword, a conditional acceptance to suck gullible people financially dry. Recently, trans female model Aaron Rose Philip called out this practice in an Instagram post. She powerfully denounced tokenising trans people, but also, the industry only furthering the careers of white and non-black trans models and confining black trans (and disabled) models to Pride Month. Although her anger is valid, and I wholeheartedly agree with her, Aaron’s post falls into the neoliberal trap that trans models’ inclusion has a communal outcome. In asking for more diversity, she risks defining individual success as communal liberation, inadvertently reducing trans people to nothing more than a marketing demographic. Now, I’m not asking her nor Alex Consani, nor Colin Jones to be TS Jesus. But I am asking Aaron to stop viewing her job as anything but that, a job. Her job doesn’t secure her community’s protection because capitalism does not complement radical, political intervention.

We are in an era of history where trans visibility is at an all-time high, yet transphobic hate crimes have surged significantly. According to an October 2023 ONS report, transphobic hate crimes in the UK have gone up by 186% in the last five years. This figure is not surprising as hate crimes are temporally coinciding with the redress on trans healthcare, where just last month, NHS England announced that they will no longer be prescribing puberty blockers to under-18s following a ban by the High Court. As well as the high-profile murder of Briana Ghey, a 16-year-old girl killed by her classmates, who would share transphobic messages about her on social media prior to her death. Spread all over social media was the battered face of Gabrielle Bardot, a model, and an Instagram mutual of mine who had succumbed to a transphobic attack in the streets of Soho, the cornerstone for rainbow flags in July. Not to mention, the invisibility of black trans women who face violence such as Naomi Hersi, who stands as one of the few documented black trans women that were murdered in the UK. Unfortunately, Victoria’s Secret hiring both Valentina and Alex, British Vogue featuring Nathan and Kai on their cover or even, the hiring of Munroe Bergdorf as its fashion editor does not translate to real life.

I write this article in complete pessimism. I spend most of my days theorising about models’ disenfranchisement that I tend to forget that there are a few who happily consent to their exploitation for thousands of pounds. That when lucrative fashion opportunities presents themselves and the focus is on one’s transness, models will jump at the opportunity to proclaim themselves as activists even when they haven’t attended a protest in their lives. That if it meant reducing transness to what fashion feels makes them look woke at the time, they will hesitate to call it out. Instead, they will share it to their hundred thousands of followers and it becomes the cultural zeitgeist at the detriment of those of us who don’t have the means to enter such an elitist industry. Because people will do anything to feel part of the Big Boy’s Club even if it means selling out their community and pretending they’re doing us a favour because they’re in the rooms. Yet, when it’s time to bring another one of us, to put us on, where are they?

Now, I’m not going to be messy and name any names this time around. I will implore that I am firing shots at every single hybrid model-activist, lightskin and otherwise, who post infographics but are absent when it’s time to organise with the community.

After all, fashion offers them the illusion of luxury by means of escapism. Even if it’s just for a moment, it allows them to re-imagine themselves within the contours of grandiosity. However misguided it seems, it’s just human nature. Last summer, I interned at a big agency and was thrusted into the elitist world I desperately wanted to be a part of. I was no longer the working-class guy when I was at the same party as top model Maty Fall. I was no longer the care leaver when I attended an exclusive Honey Dijon launch party with the face of Celine. But I was all those things when I got into a petty scuffle with a random person on a bus, who then called me a ‘batty boy’. To add insult to my bruised ego, I was also in fucking Croydon!

Bibliography

Burke, Kenneth (1941) Four Master Tropes. The Kenyon Review, Autumn, 1941, Vol. 3, №4 (Autumn, 1941), pp. 421–438.

Butler, Judith (1990) Gender Trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge. Pp. 1–272.

Mears, Ashley (2011) Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Model, UCP pp 1–328

Spillers, Hortense (1996) “All the Things You Could be by Now, If Sigmund Freud’s Was Your Mother’: Psychoanalysis and Race. Duke University Press. boundary 2, Autumn, 1996, Vol. 23, №3 (Autumn, 1996). Pp. 75–141

Zhang, Erique (2023) “She is as feminine as my mother, as my sister, as my biologically female friends”: On the promise and limits of transgender visibility in fashion media. Communication, Culture and Critique, 2023, 16. Pp. 25–32