Pretty Little Thing’s Casting Call was a Disaster, but it was Fashion Business As Usual.

Originally posted on Medium.

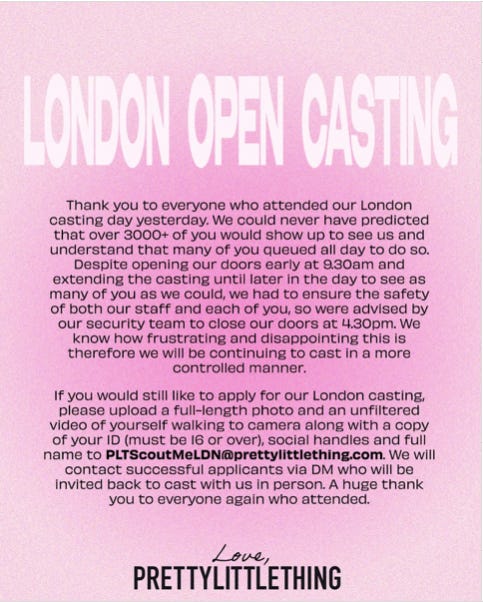

Original Post

I think we can all agree that Pretty Little Thing is one those taboo brands that you lie about owning. Nobody wants to admit that they allowed the leather craft of alleged slave labour touch their skin. Because why would you proudly tell people that you are a consumer of a maximalist concoction of nauseating flamingo-pink and cheapness? For that alone warrants an intervention at best, and complete excommunication at worst. I can’t even remember the last time the brand had garnered positive press, so it was to no surprise that this past week, the fast fashion terrorist found themselves embroiled yet again in another ethical debate on cheap labour.

On 15th May, PLT held a rare open casting in Oxford Circus, inviting aspiring models to try their shot at being the face of their new campaign, prompting many models on Tik Tok to question the brand’s financial motivations. In what was communicated as an altruistic gesture, sustainable fashion activist, Brett Staniland wrote a lengthy Instagram post expressing his suspicion that the brand wanted to cut corners and avoid paying industry standard rates. It’s one thing to get whacked by people who never really supported you anyway, but the situation became graver when the aspiring models PLT tried so hard to butter up took to social media to complain how they had been standing in line for hours in the hot sun, only to be turned away and not allowed to be seen. It didn’t take PLT long to release a damage control statement on their Instagram, inviting those that didn’t get to attend the casting to apply online. Despite the endless discourse on this matter, that PLT wasted these girls’ time because none of them were going to be chosen anyway, the more damning thing for me was that they actually did nothing out of the ordinary. It truly was fashion business as usual.

I talk about this a lot (and I know mentioning this for the tenth time feels like I’m bragging) but last summer, I interned at a prestigious modelling agency. Among many daily admin tasks, the most daunting had to be conducting the walk-ins. In fashion lexis, a ‘walk-in’ is similar to a casting, in a sense that an unsigned model, or sometimes a signed model looking for an overseas agency, ‘auditions’ to be represented. All agencies have their own process, but at this one, I was authorised to reject girls on the spot. After weeks of breaking the dreams of all hopefuls that walked through the door, I puckered up the courage to ask one of the bookers, ‘Jim’, if they had ever received any successful walk-ins. He chuckled before answering most aspiring models who walk-in will be rejected. Indeed, part of my job was to be the bearer of bad news, the town crier of broken dreams.

Rejection is the most universal sentiment in our world which binds us together. In modelling, it is the most common occurrence in a model’s career that is rarely discussed unless it is combined with a tale of perseverance and success. Because with an industry built on glamour, the foundation strengthens upon the constant exposure of winners, creating a myth that losers are rare. This helps supplement the promise of these open calls, that an industry so restrictive as fashion is finally opening its doors and perhaps one of these hopefuls may have a chance to become an insider. Ironically, even in moments of levelling the playing field, the low success rates show just how entrenched rejection is to the modelling world; that even to get a foot in the door, model hopefuls are going to be humbled at the idea, almost as a humiliation ritual. After all, rejection is at the core of elitism.

A year on from my internship, and still working in fashion, I still have yet to hear of a successful walk-in story. In fact, the most common story among models is being scouted and then signed to an agency. As I explained in my previous article, “The TS in VS: Fashion’s Commodification of Transgender,” producers of fashion create aesthetic trends by means of social communication, which contributes to the idea of the ‘look’. This process could include formal meetings with casting directors telling agencies what they’re looking for, or as Ashley Mears explains, informal social events where in belonging to a fashion community, one can rely on previous work interactions and common values, in what sociologist Patrik Aspers refers to as ‘contextual knowledge.’ It must be noted that both clients and bookers contribute to the concept of the ‘look’; one does not dominate over the other. Thus, both clients and bookers alike use this contextual knowledge to develop ‘the eye’, in other words, being able to spot a model that they can work with. This is where the use of scouts or casting directors come into play, where they set off on excavations across the world to fulfil the assignment of finding girls that match the trend or can be tweaked sartorially. I’ve sat in on meetings where bookers set a plan in motion to scout more black girls because it became a demand from clients and all their flock were out of town. In a lengthy process as such, the tastemakers already know what they want and how to get it. So, what truly is the premise of an open call?

Jim actually answered this for me, sardonically stating that the rationale behind it is to keep the window open just in case scouts may have missed a girl they liked. But he continued, ‘It’s not like they ever miss though.’ With modelling trends being so sporadic and shifting every season, walk-ins act as a cost-effective veneer to find more models. The premise makes sense, but with the failure of open calls as common industry knowledge, PLT and agencies alike using their social media to attract people to attend these open calls are a little sociopathic. Just one scroll through Tik Tok and you’ll discover a goldmine of videos from agencies probing model prospects to apply online, including basic tutorials on how to take polaroids to prep for these applications and how walk-ins work. You’ll get some captions reading, “POV: you applied online, and this is your first fashion week” as a cheeky smite to tease them into applying, plotting the idea that an application will lead to success. After all, that’s what advertising is: the luring of people to immerse themselves into a dreamscape they desperately want to be part of. In modelling, that is the overemphasis on winnings over the stark reality of rejection; this is what I call the romance of the model.

The ‘open call’ concept was doomed at inception. Most notably because I, the intern, was the one conducting them. Having the most junior person with an undeveloped ‘eye’ in charge of them proves just how little regard the industry has for them. Even in the case of PLT, the ‘open call’ was a marketing event involving free makeup sessions that had influencer and YouTuber Nella Rose present; that doesn’t scream professional nor serious casting call in my eyes. You’re so much better off standing in the middle of a busy Central London street, holding a placard reading: “You have reached the house of unrecognised talent.”

A couple weeks into my internship, I didn’t realise that I was suffering from emotional overwhelm and when I did, I lied and said I had food poisoning to which I took three days off. It wasn’t until I went to therapy that I realised I was harbouring the heartbreak of those that desperately wanted to be part of something bigger than themselves. I understood that on a stratospheric level, in fact. The voice of one girl creeps in my head sometimes. I can hear her whisper, “No, not another one,” when I approached her with a sheet which included names of all the agencies in London for her to try out. As a walk-in pro, she knew this was an offering of rejection. I was so hurt by the experience that to make myself feel better, my lies continued. I started telling girls that they were too commercial for an agency that was more editorial. I told teen girls that they were way too young and should come back at 18, knowing agencies developed girls as young as 13. I told them all kinds of lies because delivering a cup of sorrow to someone else was far too painful. When the truth would’ve sufficed. If you haven’t been scouted yet, it’s really time to look elsewhere. Because the reality is, an open call will not guarantee a modelling contract. It’s far too rare.